I met Ellen Levy for the first time in June 2014. She was in England researching a book on art and neuroscience and heard about the publication of Colliding Worlds. Having used my book Imagery in Scientific Thought in courses, Ellen had been acquainted with my work for some time and decided to contact me. We met over coffee at the Groucho Club in London. Our thoughts on art and science resonated. It was as if we were old friends. Upon learning that I’d be in New York the following week Ellen invited me to speak at NYC LASER which is a series of lectures and presentations on art and science projects, organized on behalf of Leonardo/ISAST’s LEAF initiative (Leonardo Education and Art Forum). She hosts them on behalf of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts. The session was lively with sparks flying in the Q&A. I also had the opportunity to meet others involved in artsci in New York which is a hotbed of activity in this area.

Presently Ellen’s focus is on the convergence of biology and information systems and the borders of the animate and inanimate.

She describes her fascinating research as follows:

How can biological processes and constraints be used efficiently to render forms and identify adaptive behaviors? What determines where we our attention? Can art train attention to see what is overlooked? I have grappled with these questions over three decades. In my exhibitions, both locally and abroad and associated activities (publishing, teaching, symposia, and curated projects on complex systems), I aim for new ways to address perception, generate form, and utilize methods akin to nature. Biological and human-made systems (e.g., economic and technological) are frequently compared.

My work as a microbiology technologist during the 1980s and 90s heightened my awareness of Alexander Fleming (discoverer of penicillin) and his germ paintings. With Fleming as a model, on occasion I painted with the organisms aggregating in Petri dishes. I grew them, drew and/or photographed them, and incorporated them within drawings. I subsequently scanned the assemblage, morphed it with algorithms, and printed some of the resultant images. The one reproduced here includes a reference to Mad Cow Disease (below the center), alluding to the emergence of its human spin-off as the virus entered the food chain.

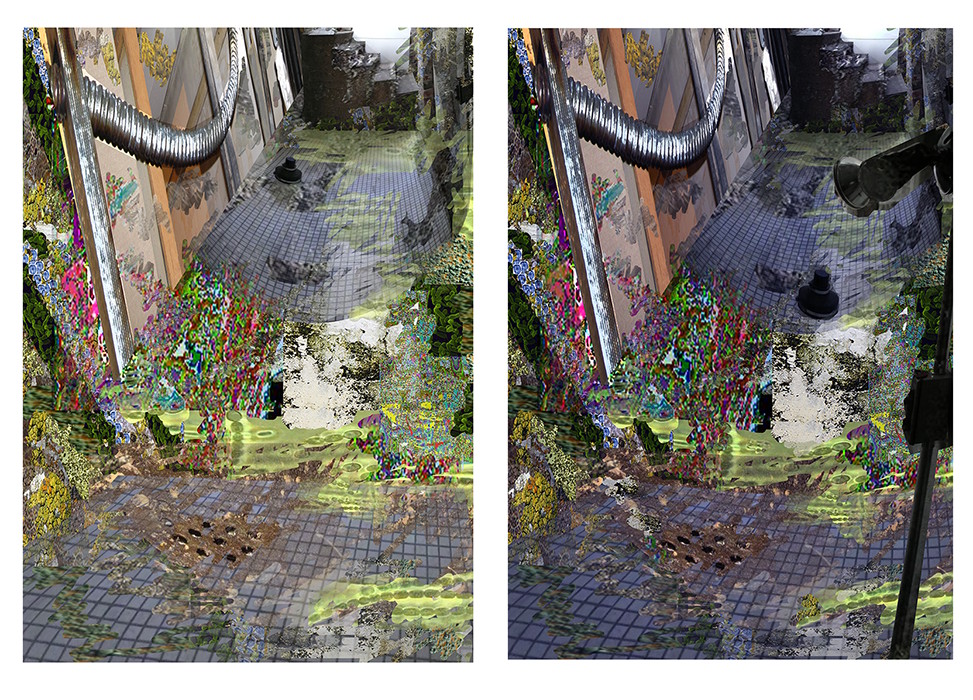

“I am currently investigating the convergence of biology and information systems and the borders of the animate and inanimate, envisioning hybrid solutions as we cope with environmental disruption. Creating dramatic changes of scale, I visualized some of the mundane objects of urban life (e.g., ventilator ducts, garbage, and health management systems) interleaved with the morphed, blown-up structures of common microbes found during Hurricane Sandy. These were exhibited at Plato’s Cave in Brooklyn during 2013. In the work below, an implicit task is directed to the viewer to identify the changes between the first and second work.

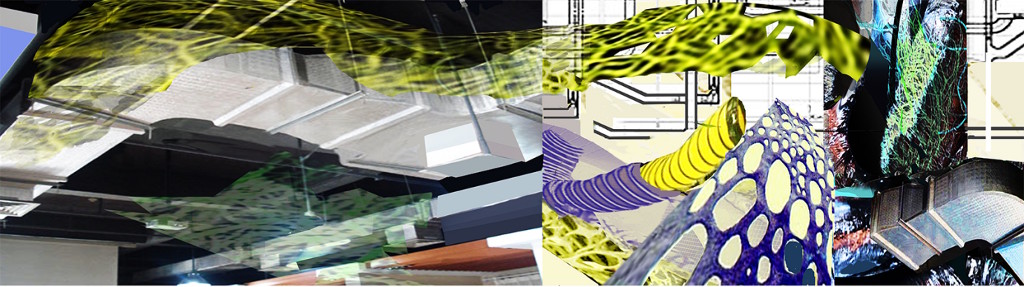

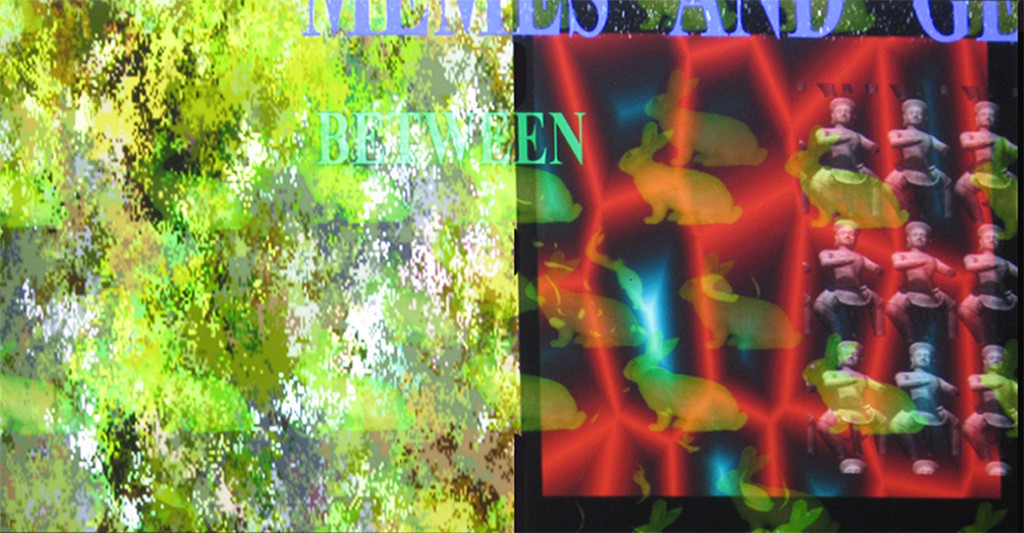

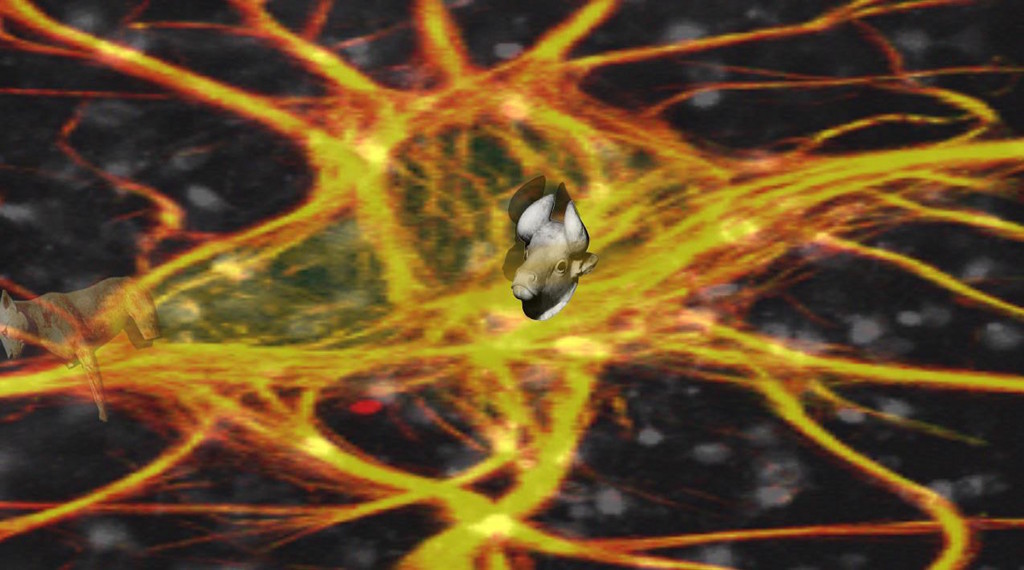

Many of my mixed media prints are accompanied by dynamic media, which initiate a different kind of viewing. They are developed to impact each other, causing each to be re-interpreted. In the stills from video below, the artificial replication of cultural objects is juxtaposed with the lichen that proliferates on the sculptures over time. Images of neurons gathered from laboratories (some gathered while working with scientists) are visually embedded with artifacts and migrate over google-like networks. At times art historical descriptions of particular antiquities culled from different periods of time replace the image altogether.

Can art ‘re-set’ habits of thinking and impact behavior? Starting in 2009 I explored our biological limitations and fallibility, researching Inattention Blindness, the phenomenon of not seeing something directly in front of you due to distraction and the constraints of attention. An animation Stealing Attention, resulted from my collaboration with neuroscientist Michael E. Goldberg, Director of the Mahoney Center for Brain and Behavior at Columbia University and member of the National academy of Sciences. Our animation was modeled after Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris’s Gorillas in our Midst, but with notable differences relating to emotion and politics. Stealing Attention was exhibited solo at Michael Steinberg Fine Arts, NYC (2009) and in several group shows, including Ronald Feldman Fine Arts (2010) and MOMA, Kiev (2011). The animation can be viewed at http://www.persimmontree.org/v2/spring-2013/stealing-attention/.

Courtesy of the Artist

The foreground consists of flashing hands and cards (the con game Three-Card Monte). The background targets are ten antiquities that were stolen from Iraq during the 2003 US invasion. A task is initially assigned to count the number of times the Queen of Heats appears. The cards flash quickly and serve as distractors. By analogy, the weapons of mass destruction served as a distraction, facilitating the US invasion of Iraq. An installation of prints of treasures being looted was shown throughout the exhibition spaces and intended to re-set the viewers’ perceptions, enabling them to see the looted objects in the background. Those who could not see the objects disappear in the animation were invited to see the entire installation and then re-view the animation. Most could then see what they had at first missed, suggesting that art trains attention. The work reproduced above shows a mixed media image of some the looting in Iraq juxtaposed with a still from the animation.

I frequently use scientific models as a starting point. For example, in the late I used a random setup of dominoes to simulate emergent global phenomena based on local social interactions. The models and drawings were inspired by Per Bak’s theories of Self Evolved Criticality. Catastrophic events (e.g., collapse of political regimes, flooding events) were suggested.

Courtesy of the Artist

A separate line of research was used in DNA and Oil (2005). It explored the landmark decision of the Diamond v. Chakrabarty case (1980) in the legal ruling that genetically modified organisms can be patented. The images that are developed are derived from an archive of patents and propelled by innovations. Each work traces the lineage of inventions related to the oil industry. Included in the references is the Exxon Valdez oil spill (1989) in which genetically-bacteria were used to no avail to help clean up the spill. In this group of works, as in others, the effects of biological modification are juxtaposed with our economic and political systems. The USPTO serves as a complex adaptive system, propelled by the ‘fitness’ of the invention (serving as an organism).”

Courtesy of the Artist

Ellen K. Levy is a visual artist juxtaposing affective representations and dynamic animations that together create unanticipated meanings; her practice encompasses experiential mixed-media installations, innovative forums, experimental projects, and writing. Levy has had numerous solo exhibitions, both in the US and abroad, including at the New York Academy of Sciences (1984) and the National Academy of Sciences (1985). Her honors include an arts commission from NASA (1985) and AICA award (1995-1996), and she was Distinguished Visiting Fellow of Arts and Sciences at Skidmore College (1999), a position funded by the Luce Foundation. Her work was included in Petroliana at the 2nd Moscow Biennale (cur. E. Sorokina, 2007), Weather Report: Art & Climate Change at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art (cur. L. Lippard, 2007), and Gregor Mendel: Planting the Seeds of Genetics at the Field Museum, Chicago (cur. C. Albano, M. Wallace, adv M. Kemp, 2006). As guest-editor of an issue of Art Journal in 1996 she introduced the topic of art and genomics to a broad academic audience and has since published widely on art in relation to complex systems. Levy is currently Special Advisor on the Arts and Sciences at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts, and she was President of the College Art Association (2004-2006) before earning her doctorate from the University of Plymouth for her research on art and attention.