This dramatic line of research explores the body and how it will undergo radical changes in the future – in other words, what it means to be a body.

[Note: Page numbers refer to pages in the book.]Stelarc

Stelarc’s works are astounding examples (pp. 199-201). Many border on science fiction. Exoskeleton is a six-legged, pneumatically powered walking machine constructed for the body. With Exoskeleton Stelarc explores the human-machine complex – what it is to be machine-controlled, and to have prosthetic bodily extensions.

Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana

Photographer – Igor Skafar

Muscle Machine is a six-legged walking robot in which Stelarc is completely encased. Five metres in diameter, this human-machine system is pneumatically powered using fluidic muscle actuators. Once in motion, human and machine are fully integrated and move as one.

Gallery 291, London

Photographer – Mark Bennett

Stelarc has demonstrated the left “ear” implanted on his left arm any number of times (see Insert in book). This one combines his superb talent as performance artist.

Scott Livesey Galleries, Melbourne

Photographer- Claudio Oyarce

Nina Sellars

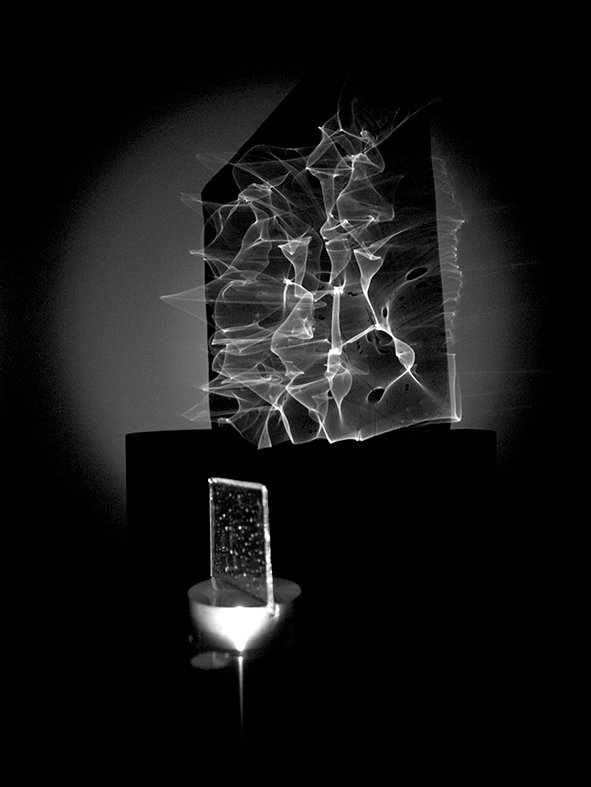

Although it featured in a biology-influenced art exhibition, to me Nina Sellars’s Lumen borders on physics-influenced art with its abstract forms generated by the play of mirror and laser.

Lucida is a recent development on Lumen that uses two image-generating devices making the resulting images even more abstract than in Lumen. Her goal is to immerse the viewer in microscopic views – which can also seem to be of the cosmos or from the unconscious – while allowing the audience to see the technological components.

Davide Angheleddu

Davide Angheleddu “gets inspiration from nature, particularly from nature sublimely described in the book Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature) by the German philosopher and biologist Ernst Haeckel” (p. 192). At GV Art his works were hung in the outdoor garden. Visitors enjoyed the crisp, perfect, organic shapes, sculpted using digital techniques. They are about 2 feet in length. Here are examples:

Recently Angheleddu has turned to physics-influenced art with work based on the discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN’s massive Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in 2012. This discovery was monumental because the Higgs boson is essential to understanding why elementary particles have mass. Angheleddu explored its discovery from the artist’s viewpoint.

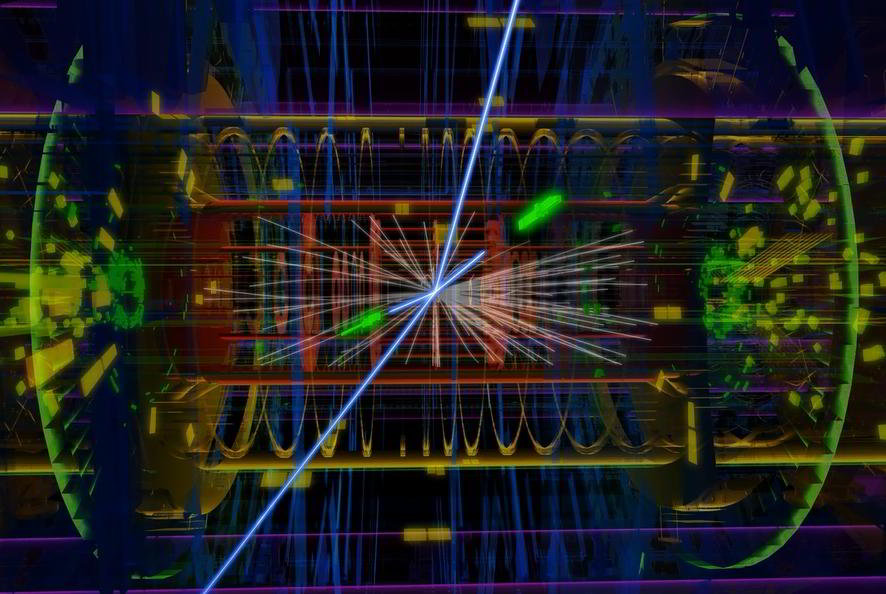

The LHC is a huge ring twenty-seven kilometers in circumference running through Switzerland and France. In it swarms of protons moving in opposite directions are accelerated to near the speed of light and then smash into each other. Physicists hoped that the Higgs would be among the debris but knew this would be a rare event. In fact they had calculated that it probably occurred in only one to ten billion collisions. The ‘gold plated’ event was found in data gathered by the behemoth Atlas detector, 46 meters long, 25 meters in diameter and weighing in at 7,000 tons. The Higgs made its appearance in the event shown in the image below, constructed using computer graphics from the original tracks of the three-dimensional CERN file. The Higgs’ signature – or finger print – are the two blue tracks resulting from its splitting up into two electrons and two muons (a specie of the electron).

This image is actually a frame from a video made at CERN toward explaining the experiment in which the Higgs was discovered.

Courtesy of CERN

It jolted Angheleddu’s artistic imagination.

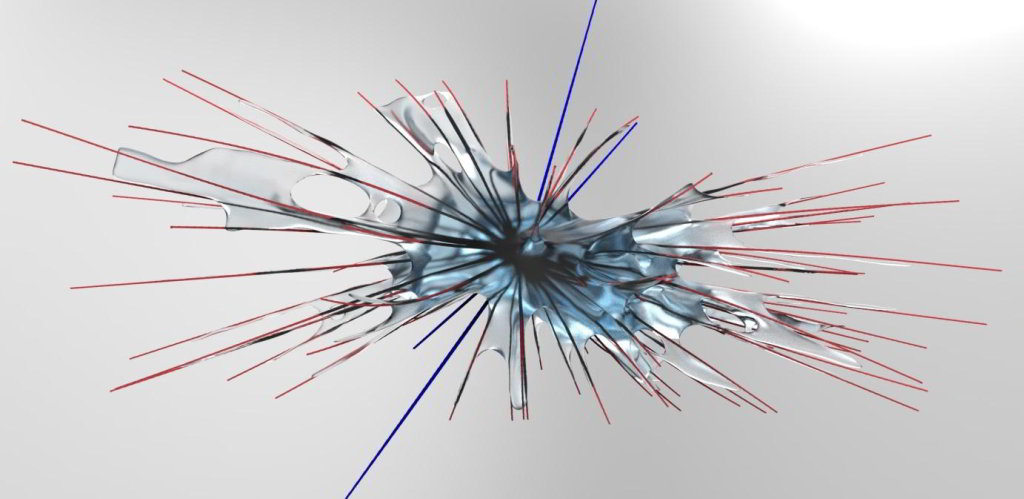

Sculpting with a laser, he produced a set of stunning aluminum sculptures of the starburst pattern shown above which signals the Higgs’ production. Here is one of them.

Artist: Davide Angheleddu. Size 35 cm, weight 1 kg.

It is strikingly similar to Josiah McElheny’s glass sculpture An End to Modernity (p. 133 and on the cover of Colliding Worlds). McElheny depicts the creation of our universe from the explosion of space 14 billion years ago in what we call the Big Bang. Angheleddu ‘turns inward’ and depicts the creation of the Higgs under conditions identical to the Big Bang, produced in the LHC.

Both phenomena can be traced to star bursts. Perhaps, as the ancients believed, the macro- and micro-universes are indeed mirror images of one another.

Helen Pynor

Normally we prefer not to look at organs. Helen Pynor does. She “uses them to make beautiful and thought-provoking works of art,” as in Liquid Ground 6 (p. 197). Her art has always been controversial.

Among her other works is this dramatic and poignant video, The Body is a Big Place, in collaboration with Peta Clancy. They explore organ transplantation and the line between life and death. Pynor and Clancy explain:

The Body is a Big Place

Helen Pynor and Peta Clancy

The Body is a Big Place is a large-scale, immersive installation developed through collaboration between artists Helen Pynor and Peta Clancy in collaboration with scientists. The work explores organ transplantation and the ambiguous thresholds between life and death, revealing the process of death as an extended durational process, rather than an event that occurs in a single moment in time. The work’s title refers to the capacity for parts of the body to traverse vast geographic, temporal and interpersonal distances during organ transplantation processes. As part of the installation a fully functioning heart perfusion system was used to reanimate to a beating state a pair of fresh pig hearts during 2 live performances. Rather than sensationalizing these events, the artists sought to encourage empathic responses from viewers, opening up the possibility of a deeper awareness of viewers’ own interiors. Performers in the work’s projected underwater video sequences were members of the organ transplant community in Melbourne, individuals who have received, donated, or stood closely by loved ones as they received or posthumously donated human organs.”

Artists: Peta Clancy and Helen Pynor

Sound: Gail Priest

Collaborating scientists: Professor John Headrick and Dr Jason Peart, Heart Foundation Research Centre, Griffith University, Australia.